By Suzanne DeMallie, originally published in the August, 2021 issue of Equity & Access

Every day, millions of children walk into classrooms under the premise that when their teacher speaks, they will be able to hear and understand what is being said. But in reality, students often miss hearing parts of sentences or words, or fail to distinguish between similar sounding words, compromising their ability to understand and learn.

Students spend the majority of each school day engaged in auditory learning – listening to directions and instruction from their teachers and listening to the questions, comments, and answers from their classmates. Yet, the typical classroom fails to support the auditory needs of its listeners. The reasons for this deficiency can be lumped into three categories: poor acoustics, immature auditory neurology, and students with greater speech perception needs. Here’s a look at how each one of these factors influences hearing and ultimately academic achievement.

Poor Acoustics

Acoustics is the impact that the physical environment has on the ability to hear. There are primarily three components of acoustics: background noise, reverberation, and the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The SNR is the difference between the volume of what you are trying to hear (the teacher’s voice) over the other noise in the room – such the hum of HVAC equipment, students whispering, feet shuffling, and pencils dropping. It is the most important determinant of speech intelligibility – that is, whether or not the listener can understand what he or she is hearing.

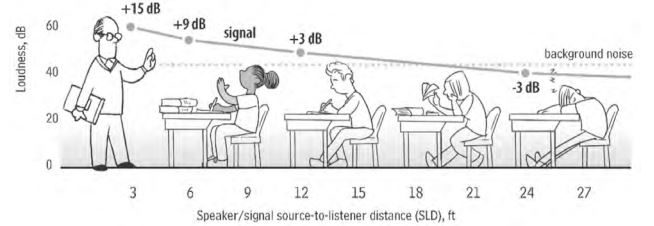

It is Probably No Surprise That Most Classrooms Have Poor Acoustics

The American Speech Language Hearing Association (ASHA) has specified that background noise should not exceed 35 dBA (in an empty room) and reverberation should not exceed .6 seconds. However, numerous studies have revealed classrooms that exhibit excessive noise and reverberation far beyond those specifications. According to ASHA, the normal hearing child needs the SNR to be at least fifteen decibels for speech intelligibility. The problem is while high levels of background noise remain relatively stable around the classroom, the teacher’s voice drops in volume over distance. The result is that students not seated in close proximity to the teacher are at a significant disadvantage.

Immature Auditory Neurology

While acoustics is important for all listeners, children have unique hearing needs that require even better acoustics than an adult in order to achieve the same level of comprehension. According to the book, Sound Field Amplification Applications to Speech Perception and Classroom Acoustics, the neurological auditory structures are not fully mature until age 15; thus, a child does not bring a complete neurological system to a listening situation. This means that children are slower to process the sounds they hear and cannot always “fill in the blanks” for sounds and words that are missed or muffled. Adults, however, can fill in the gaps and make sense of what they are hearing based on context and a historical language ‘database’ that has been developed over many years. This is referred to as auditory or cognitive closure. Sometimes this process occurs so automatically that the adult isn’t consciously aware it is happening. Children just do not have the neurology for cognitive closure.

For this reason, they need an optimal auditory environment so that they can detect, distinguish, identify, and interpret all of the sounds they are hearing. These steps ultimately lead to comprehension or speech intelligibility.

Greater Speech Perception Needs

Poor acoustics and immature auditory neurology impact all students regardless of hearing ability. Additionally, there is a subset of the student population who have even greater speech perception needs. Amongst those are students with hearing impairments and auditory processing deficits.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 20 percent of children up to 18 years of age are affected by a hearing loss. The book, Sound Field Amplification Applications to Speech Perception and Classroom Acoustics, cites an additional 10-15 percent of primary-level (kindergarten through second grade) children who suffer a temporary hearing loss from fluid relating to middle ear infections, one that commonly extends for weeks or months. Another five percent of school-age children, or approximately 2.5 million children, are estimated to have an Auditory Processing Deficit (APD) which means that their ears can detect the auditory signals but their brain has increased difficulty interpreting and making sense of what they hear.

Other students with perfectly normal hearing and processing abilities have greater listening needs. English Language Learners (ELLs) fall into this category. ELLs represent approximately ten percent or five million students in the US. Their limited English proficiency requires that they hear each part of a word to be able to discriminate the English sounds, some of which may be very different than or even non-existent in their native language.

A Simple Solution

If the auditory environment by itself, cannot satisfy the hearing needs of its listeners, how then can schools effectively convey the teacher’s verbal instruction, especially to students not seated in close proximity? The answer is as simple as a wireless teacher microphone and one or more speakers in the classroom.

This technology amplifies the teacher’s voice by about eight to ten decibels, and then delivers that voice to areas of the classroom that otherwise would hear a substantially ‘weakened’ voice. If multiple speakers are placed in the classroom ceiling, the teacher’s voice can be evenly distributed much like a shower dispenses water. The result is that all students, regardless of proximity, get to clearly hear their teacher. Essentially, every student gets preferential seating without the required accommodation.

According to ASHA, sound-field amplification technology has been used in classrooms since the inception of the Mainstream Amplification Resource Room Study (MARRS) Project in 1978. MARRS was intended to be a three-year study on fourth- through sixth-grade students with minimal hearing loss, coexisting learning deficit, and normal learning potential, conducted in the Wabash and Ohio Valley schools in southern Illinois.

Approximately half of the students remained in regular classrooms and the other half were taught in rooms where teachers used sound-field FM amplification systems consisting of wireless microphones and two speakers. The most significant result of the study was that ALL students, not just those with a hearing impairment, showed the greatest and most rapid increase in academic performance when taught in the room with the teacher microphones.

Benefits to Students and Teachers

Since this initial study, several others have validated the benefits of the technology for all students which include increased academic achievement, improved literacy, improved attention, and reduced behavior problems. Ray (1990) and Sarff, Ray, and Bagwell (1981) found that “the most cost-effective and acceptable technology for facilitating learning in a typical school classroom is the use of a sound field FM system.” Today’s technology uses infrared rather than FM waves and most systems include hand-held microphones for the students to use.

The benefits of using this technology are enjoyed by the teachers themselves. Teachers, who talk for extended periods of time each work day at a volume above a conversational level, are twice as likely as non-teachers to suffer voice problems from fatigue and strain on the vocal chords. One study found that 50% of US teachers experienced three or more voice symptoms that negatively impacted their ability to teach. Subsequently, teachers are often absent from work for a vocal related issued. Evidence suggests that teacher microphones can reduce vocal strain and thus absenteeism; thereby saving on administrative costs and stipends associated with substitute teachers.

This technology not only enhances the teacher’s voice but also the school climate. It creates a calm environment for both students and teachers. It allows teachers to speak in a conversational tone which is more conducive to learning and behaviors. Increased access to the teacher’s voice means that students need less repetition of instructions and are more on-task. The combination results in students who are better behaved and more engaged, ultimately leading to improved teacher job satisfaction.

Advocate for the Integration of this Technology in Your Schools

We have to recognize that the teacher’s voice is one of our greatest instructional tools in the classroom. Therefore, it is important that each child have equal access to that voice and do everything possible to preserve the teacher’s health.

If you would like to advocate for teacher microphones and speakers in your school or district, please share this information with your school’s administration, PTA, School Improvement Team, Board of Education, local politicians, local teacher’s union, and area specialists such as speech and language pathologists and audiologists.

Every child deserves to hear their teacher, and every teacher is important enough to be heard!

Learn more about Suzanne’s book, Can You Hear Me Now? at Amazon.com.

The American Consortium for Equity in Education, publisher of the "Equity & Access" journal, celebrates and connects the educators, associations, community partners and industry leaders who are working to solve problems and create a more equitable environment for historically underserved pre K-12 students throughout the United States.

- American Consortium for Equity in Educationhttps://ace-ed.org/author/admin/

- American Consortium for Equity in Educationhttps://ace-ed.org/author/admin/April 23, 2025

- American Consortium for Equity in Educationhttps://ace-ed.org/author/admin/

- American Consortium for Equity in Educationhttps://ace-ed.org/author/admin/